July 1, 2024

Hi, everyone. Welcome to the Old Observatory. I'm Julia, an astronomy student at Leiden University, and I will be your tour guide today.

This is how I started tours for three years. Guiding tours in the historical astronomy building was an exciting side job. I used antique telescopes and pulled out historical anecdotes as a fun party trick. I never thought about concrete skills I learned beyond the vague "gaining public speaking experience."

My stint as a tour guide re-entered my mind when touching up my CV. Not long after, I was preparing a work presentation about creating ML datasets. A thought struck me: I'm using skills I learned as a tour guide. Without any serious presenting courses, I had learned to build a database of topics, factoids and anecdotes. I practised these many times until I found the right words. I remembered everything by connecting anecdotes to different parts of the building. With those tools in my pocket, I adapted tours to the audience on the fly.

Thanks to these skills, public speaking was fun and not hard at all. I don't see a reason why you can't use them for your presentation. I share four valuable skills I learned as a tour guide before I knew much about presenting. I explain how to use them in presentations and why they make you a more confident speaker.

An image of me standing on the stairs used for observing through the 10-inch telescope at the Old Observatory in Leiden. You can flip up each step so you can sit down easier at lower steps.

I'll admit it. Most times, I practised work presentations, and I forced myself through the talk once or twice. I checked the timing and called it a day. But I wanted to try something new: practising parts of the presentation. A storytelling course teacher and professional presenter said she does it that way.

I practised my ML datasets presentation for a few hours. Instead of talking through it linearly, I looked for awkward, lengthy, or unclear explanations. I kept repeating these parts until the words came out right. Sometimes up to ten times! Before practising, I prepared the presentation thoroughly. Talking through it exposed all the holes I had missed in writing. And sometimes that needed a few tries, just like you rewrite texts. Practising this way made a world of difference. I spoke confidently and with fewer 'uhms.'

Reflecting on the presentation (See review bog), I realised I used the same strategy as a tour guide. I learned all the stories and facts about the Old Observatory. I cemented them in my mind by repeating them many, many times--first on my own, then on actual tours with different people. After enough tries, the stories about Einstein's visits and frosty nights of stargazing came out on their own. All I had to do was say the first few words.

Me looking up at the 10-inch telescope in the Old Observatory, while I give a tour.

These anecdotes were the building blocks of the tours. The same concept of blocks is introduced by Duncan Yellowlees in his "Prep your talk" email course. The idea is to make a personal database of topics you can talk about. You build presentations (or tours!) by choosing a few blocks that fit your message, available time and audience. As a tour guide, I learned that by practising the blocks again and again, they stick in your mind, and you can pull them out, just like that.

PowerPoint slides cue the next topic for the speaker in a presentation. When you give a tour, you have something much better: a physical building and cool objects like telescopes! I tied every anecdote to a room or object:

As I guided a group through the building, the objects and rooms would remind me of the stories in my head. It was up to me whether I wanted to:

So, I build the "talk" during the tour. The "slides" are just a backdrop and a landmark in your memory. Use actual slides the same way: a prompt to start your story on the one hand and extra visual support for your audience. If you've practised your blocks, you won't have to rely on lots of text to remember what you meant to say.

Here's one lesson I learned the hard way. During a tour, I told an anecdote about a famous astronomer. Afterwards, one of the group members came to me and told me that the astronomer was his grandfather. My face got hot with the fear I had said something wrong. I felt stupid: me, a stranger, telling this person an anecdote about his grandfather.

On the next tour and all the ones after, I first asked how much the group knew about astronomy. It's a simple question that prompts anything related to astronomy. Anyone related to a famous astronomer will probably mention it. The key here is not to be afraid to ask how much people know. It adds interactivity and helps you deliver a personalised tour.

One day, I guided a big group of retirees who studied law together in Leiden. Previous groups of retirees wanted history, but this group was very different. I led them up to the observatory's roof to take a group photo while it was still light out. Then I gave them a choice: do you want to know about the history of this place, about astronomy, use the telescopes?

Well, they wanted to know about astronomy. What is dark matter, what are black holes, and what's the difference between a star and a planet? They were as excited as a children's birthday party. I answered questions for most of the tour. It was such a unique and exciting experience.

Some people love to hear the building's history, while others crave answers about stars and black holes. I asked people what kind of tour they wanted. Your goal isn't just to deliver your message (in this case, astronomy is exciting!); it's also to create a memorable experience for your audience.

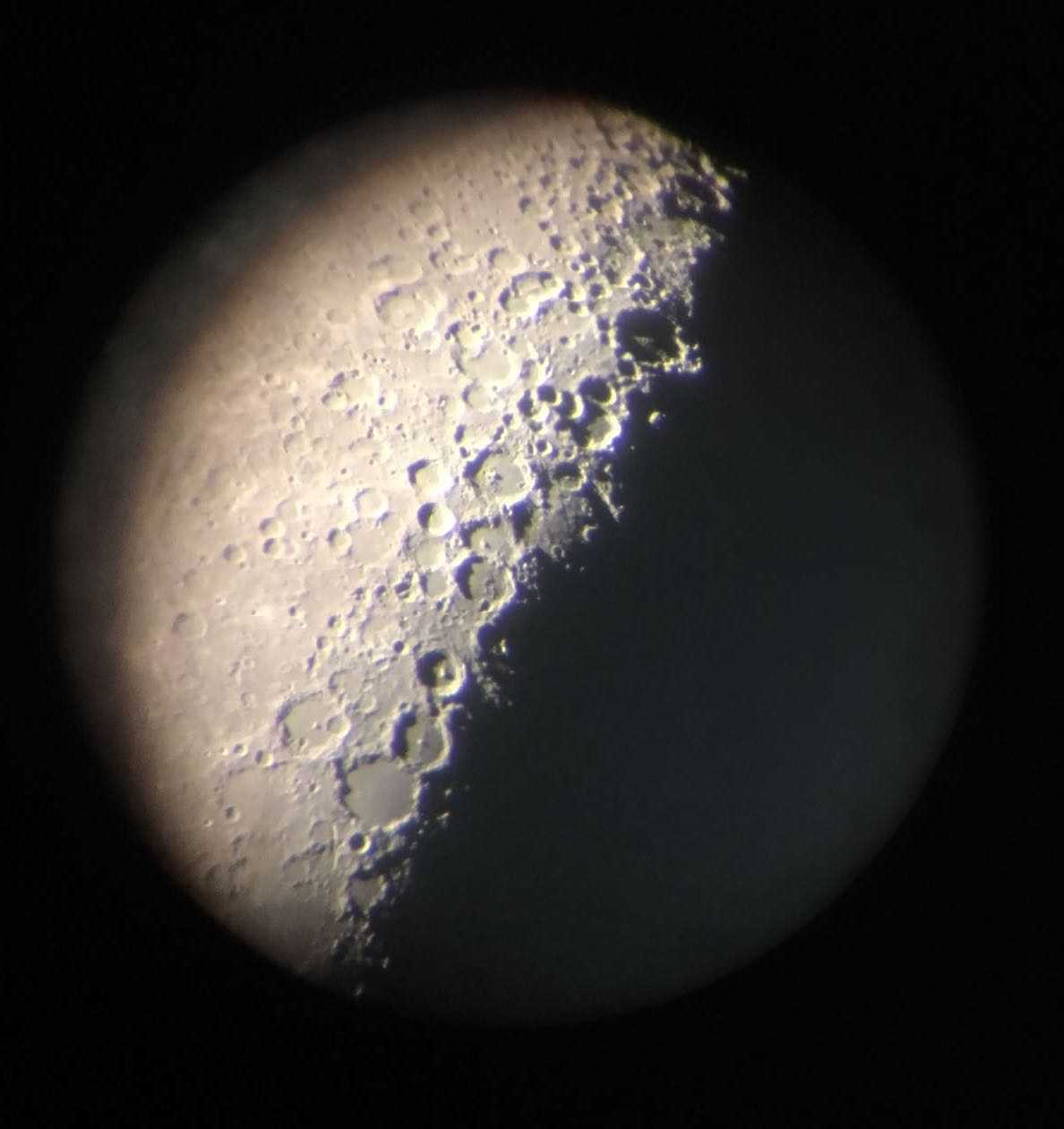

This is a photo of the moon I took with my mobile phone through the 10-inch telescope at the Old Observatory. The telescope has a motor to track the movements of the sky, but it's not perfect and the moon moves faster, so it's a bit tricky to take a picture!

The bottom line:

Guided tours aren't presentations. There isn't always a straight story to tell. You can't really prepare for an audience because you don't know who'll show up. Guided tours are also way more interactive. In short, you need to improvise a whole lot more in guided tours.

You will need to improvise in some talks, too: when the audience is different than you thought or when the event changes at the last minute. In presentations, it's not that common to ask audiences up front what they know or want. But you can keep an eye on the audience's engagement and questions to tweak your talk on the go. These are surprise opportunities to make your talk better beyond what you were able to prepare.

Being a tour guide taught me that the core is knowing your material very well. Only then can you use aids like objects or slides to remind you what to talk about. Your talks will be more confident and fluent, and you'll save time preparing future presentations. If you've prepared well, adapting to the audience doesn't have to feel like improvisation at all.