June 7, 2025

Do I put this in the methods or the related work? What makes my writing informal? How do I order the results section? I get these writing questions all the time. Many computer science students struggle with the same academic writing problems. In this blog, I share my most-repeated advice and give you lots of actionable tips to improve your academic writing.

Academic writing is the written communication of research ideas or findings, targeted at other researchers. Academic writing is more formulaic than most students know: we have strong traditions for the content, structure, and style of the writing. We’re expected to learn this, yet many university programmes don’t have a dedicated writing course for undergrads. We learn writing slowly, painfully, through feedback on our assignments. Our computer science students at Leiden University need to do three forms of academic writing:

In this blog, I’ll focus on reports/papers, but you can apply most of these lessons to proposals and theses, too. I have three goals:

I will cover how to decide what information goes in (content), in what order to present it (structure), and how to choose the right words (style). I will also write about the process of writing: from the blank page to your first draft, and what happens when you submit your writing to your supervisors. Finally, I’ll show you two real examples of how I would grade my own proposal and corresponding paper right now.

The first thing people struggle with when writing papers is deciding what to put in which section. I remember I was especially confused about the difference between the related work and the methods. Let’s look at the parts of computer science papers and what information a researcher reading your paper expects to find in each one.

Computer science papers always have the following sections (though they may have different names):

The abstract is a mini-summary of your paper, designed to make people want to read the paper. It should briefly mention the research field, what problem you solve, the methods you use and the most important findings. Finally, briefly state the broader relevance of your results.

The introduction sets the stage for the rest of the paper. It needs to:

After reading the introduction, the reader should be convinced that there is a problem to solve and that your approach is a promising solution.

Do you ever get angry when you watch a movie, and the main character is suddenly saved by something entirely new, like magic or a weapon that appears out of nowhere? This is a plot device called deus ex machina. It’s an unoriginal and often unsatisfying end, and it can mess with our academic writing as well.

The reader must learn early on what they can get out of this paper: is it a methods paper, are the results positive? If you fail to mention something important, like a key part of your method or a surprising result, the reader can feel confused or even manipulated. Therefore, the introduction has to at least hint at every key method, result, or other plot twists.

The key to a strong introduction is to make the problems as specific as possible. The broader the problem, the more evidence you have to provide to show that you fixed it. More AutoML4EO papers than I can count present ‘designing neural networks is hard’ as the knowledge gap, but then only evaluate their methods with 1-2 specific satellite image datasets. In this case, the scope of the introduction is too broad for the evidence presented. You don’t solve the problem of design of ALL neural networks by showing results only from satellite image datasets. Instead, present a knowledge gap specific to this type of data/problem.

If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

His words emphasise that all our research is only possible because of the work of people before us. In the related work, we summarise the previous research the reader needs to know to understand our contributions. But the related work is also more than that: it shouldn’t just be a chronological summary of the field. The related work should set out how your work fits in with related papers. What do you approach the same way? What is different? Further flesh out the knowledge gap in the related work: which alternative approaches are you not considering, which questions are people working on? You don’t have to explain why you don’t do all those other things. The point is more to clarify overlaps and differences with other papers.

Now, I always think the background is a strange section. It is the place all essential information goes that does not semantically fit into the introduction, related work, or methods. The background lays out the theory and foundational information needed for your peers to understand your thesis. Think mathematical formulas and notation, and domain knowledge about the data you have learned during your project but your peers might not know (like a subsection about satellite data). So in contrast to the related work, this is not about other methods.

The methods section has two broad goals:

The first mistake people make is to focus too much on previous work. In this section, your proposed solution should take center stage. Avoid lengthy descriptions of pre-existing methods. These may fit better in the introduction or related work. Or, you might not need that much detail and it can be enough to just refer readers to the original paper.

The second mistake is not making clear which bits are your solution and which methods were invented by somebody else. Many people accidentally use language that signals to scientific readers that you invented something, when really you just applied an existing method. This can be considered improper credit attribution, which is a form of plagiarism (even when it’s unintentional). Avoid this by:

Finally, it is very helpful to add diagrams and/or a pseudoalgorithm to show your methods. It is sometimes easier to understand than a textual description.

The empirical setup of a machine learning research project is incredibly important. It doesn’t matter how persuasive your idea is if the experimental design is shaky. In the empirical setup section it’s your job to convince readers that you did everything you could to make the evaluation of your methods as solid as possible. Describe the research questions, data, baselines, and experimental details.

The empirical setup is mostly a very dry section with lots of details. A few do’s and don’ts:

The results section seems to speak for itself: it’s where you show your results. But it’s not only that! In computer science, the results and analysis are merged into a single section. Therefore, the results section shouldn’t just display the results but also discuss the interpretation, implications, and the limitations. It’s very important to not only describe what the tables and figures show, but to draw conclusions from the results. What does it mean that method A is better than method B?

The conclusion is a super-short section at the end of the paper that looks a lot like the abstract. Where the abstract is a sales-pitch designed to draw people in, the conclusion is more like a short report. Like the abstract, it’s a stand-alone summary of your paper: you have to be able to understand it without having read the rest of the thesis. Be aware that researchers often don’t read theses and papers linearly. It depends on the person, but often people will read the abstract and conclusion first before reading the rest. So don’t dive straight into the conclusion of your results, briefly repeat the topic, problem, and solution. Finally, mention ideas for future work. These can be things you want to work on, or research directions for other people opened up by your work.

Structure does not only refer to the sections of a paper. Many beginning researchers do not realise there are strong conventions for structure within each section and paragraph, too. A strong structure helps readers navigate the text and follow your argumentation. Academic writing follows the inverted pyramid: start with a general introduction, getting increasingly specific as the section progresses.

Sections start broader than you think. The most common structural mistake is skipping introductions to each section. All sections except the abstract, introduction, and conclusion should open with a few high-level sentences describing the contents of that section. As a result, there shouldn't be any stacked headings (e.g., a subsection heading immediately following a section heading). This introduction helps orient readers, while jumping into details straight away can leave them confused.

The commkit from the MIT EECS communication lab has a great resource on the structure of different sections in computer science papers. I won't repeat all of it here, but I highly recommend you check it out. Here, I want to say some more words about the structure of the introduction, methods, and results. Finally, I will give you tips on constructing better paragraphs.

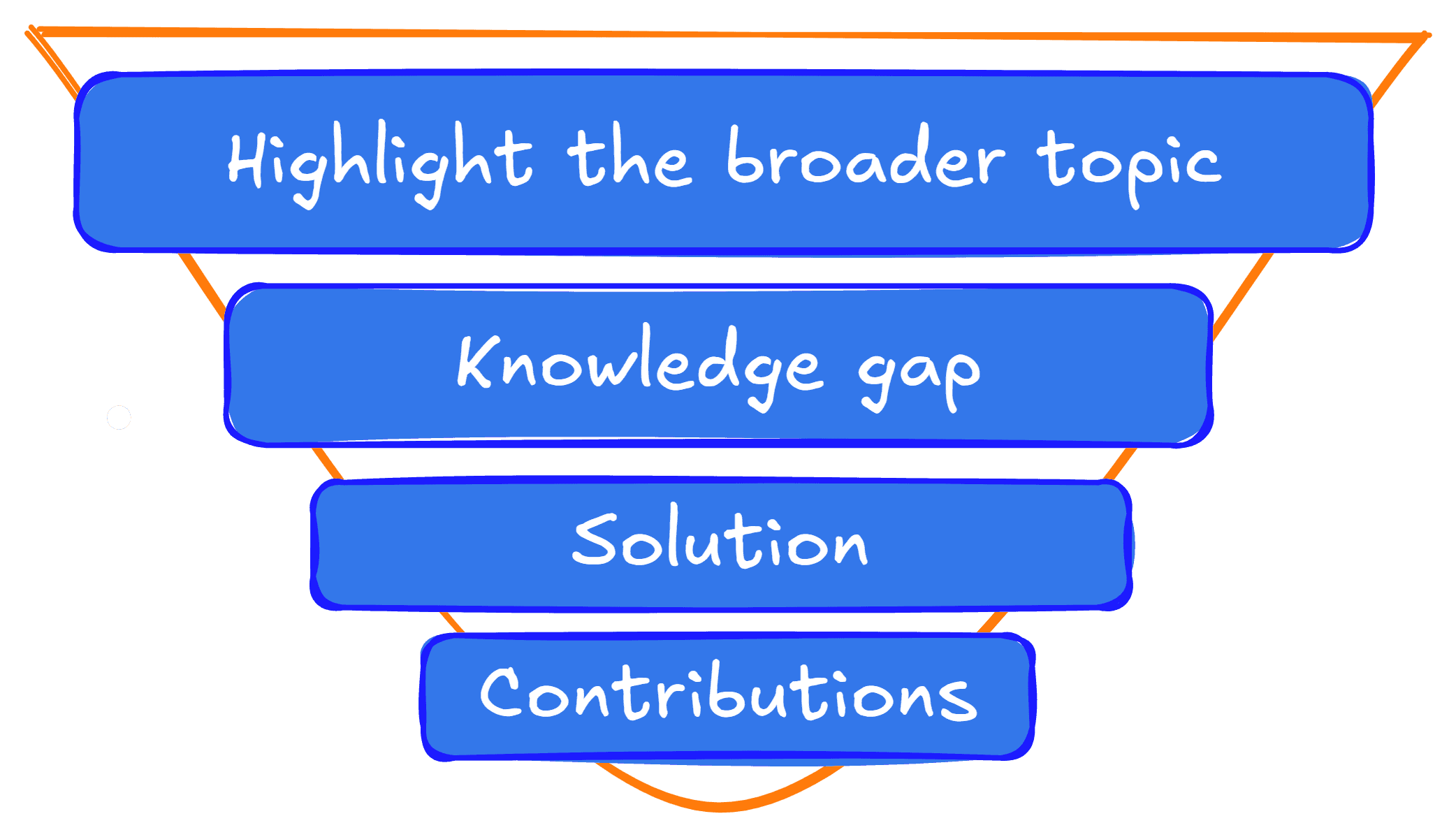

The introduction section is one of the exceptions to rule of introductions. It mostly follows the inverted pyramid going from the general topic up until the contributions. Introductions to long pieces of writing then often have a one-paragraph outline of the rest of the thesis. This is the one case where we don't want to start with an outline, because the introduction needs to be engaging and outlines are a bit boring.

The introduction doesn't just follow the inverted pyramid, it also has a very particular structure used throughout all of academia (not just ML): the CaRS structure. CaRS stands for Creating a Research Space. There are three steps:

I cannot stress enough how important it is to focus on your own methods. Don’t go on too long about previous work, there will be space for that in the related work. Steps 1 and 2 should only be long enough to create the need for your solution. Explain the key insights and strengths of your method, don't wait until the methods section!

The inverted pyramid for the introduction. Apply the same principle of going from general to specific to any other section.

Choose a logical way to group related methods in the related work:

Which one you choose depends on your project. In any case: add a short introduction at the top of the related work introducing the categories. Explicitly link each group of related works to your approach. If this is vague, read a few papers and highlight every mention of the proposed method in the related work.

The methods section often hides another structure: the problem statement. If it's not a separate section, it's usually the first paragraph of the methods section. The problem statement is a formal description of the task (e.g., image classification) using mathematical notation. The scope of the problem statement should match your solution. Make the problem statement as specific as your method. For example: a problem statement about standard image classification is not specific enough for a paper about data fusion. It sounds hard, but you almost never have to draft it from scratch. Papers solving the same problem should have similar problem statements, even if their methods are very different.

Organise the remainder of the methods section by method components. For example, if you have a method with three components, you can have three subsections describing each component. Name the components and explain how they are linked in a short introduction. Each subsection should start with a high-level description of the component, then go into the details. Inverted pyramid!

There are different ways to structure the results section. It depends on the project what fits best. I like to organise the results by research question. Another option is to split by dataset, if you evaluate multiple. The best structure for you is the one that:

The second tip is to order the subsections by importance. Start with your most important, ‘biggest,’ results, moving on to the smaller results that nuance the main result. For example, if you combine many different methods, start with the results of the full method (all X components) and end with ablations (turning individual components on and off).

Paragraph structure is another very common mistake in academic writing. Here’s what goes wrong:

There is nothing inherently wrong with short paragraphs, but it’s in academic writing and persuasive writing in general, one paragraph should describe one full idea or argument. Don’t compare academic paragraphs to blogs, news articles, and columns: those are different genres with different conventions. Compare your paragraphs with published papers if you are concerned. Before pressing enter, ask yourself if you’re moving on to a new argument or topic. If not, restrain yourself!

Just like papers and sections have very particular orders, researchers also expect a certain structure from paragraphs. Generally: start with the topic, list arguments or supporting information, and end with a link back to the main argument or the next paragraph. There are many different models, I really like the TEECL structure. It is a bit confusing and hard to get used to at first (it can help to practice by asking an LLM to rewrite a few of your paragraphs in that structure). Practice is key.

I want to stress the importance of the final sentence, the ‘L’ in TEECL that stands for Link. It refers to a much-forgotten sentence at the end of persuasive paragraphs. Without this sentence, readers have to figure out themselves how the information you presented is relevant to the topic. You need to make that explicit. To learn how, I suggest tmarking the last sentences of the paragraphs in the related work and results sections of a few papers. This will help develop a feeling for how much to explain explicitly.

Writing tone & style are hard concept to grasp. Some people have almost perfect academic tone from the start, others write very informally. Tone is how the text sounds like: is it your professor speaking, or the person behind the bar? You learn tone by reading lots of papers. Writing style is harder to pick up passively. Most of us have to work at it actively. Writing is a craft that requires skills, just like playing sports.

The biggest tone error is informal writing. Academic writing is really formal, which means two things:

Then there are some small things, like avoiding contractions (can’t, don’t, won’t) and spoken language, which is considered informal.

Writing style is the subject of many books and courses. People devote their life to honing their style. I cannot do this topic justice here. Here are my a few tips:

Writing is much more than putting the right words in the right place. Writing starts when you’re doing a literature review, when you’re designing a problem statement. Writing starts in your head with research and design. However, that doesn’t mean you cannot start writing early in your project. When do you start writing? Where do you start? And when is it finished?

My biggest piece of advice regarding your thesis research is to resist the urge to start programming and experimenting right away. Every student I’ve worked with, myself included, felt daunted by the prospect of their first large research project and wanted to get ahead as soon as possible. However, it’s very important to design your research first so you don’t spend weeks running random experiments and realising at the end it’s not really going somewhere (or worse, someone else already did the same thing).

A good first step is to draft a research proposal. A proposal does not have to be written perfectly, but has to describe the core idea and resources needed. A proposal should highlight:

By itself, it’s not a very long piece of text (maybe 2-10 pages) with lots of bullet points. Take enough time to think carefully about your design. Don’t rush this foundation, because if the problem statement & solution (including motivation) aren’t strong, experiments won't fix it. Take at least a week, probably more. Read more papers, do preliminary data exploration or very small-scale experiments, or talk to your supervisors if you struggle coming up with a concrete problem or research question.

Once the design is set, start implementing and running your experiments. Expand the sections from the proposal as you go. For example, write the methods after you’ve implemented them, and update the text as your research changes. (the plan always changes). Some people recommend to write the introduction last. Personally, I think you can write it already early on as long as you already designed the problem statement. I do recommend to leave the abstract and conclusion until the very end (because they are summaries of the rest of the paper).

Earlier I mentioned comments very briefly. In reality it can be one of the harder and more frustrating parts of writing. I was certainly surprised by it. Supervisors can leave conflicting comments, especially if they are from different disciplines. And sometimes you don't understand what is asked of you.

Here are my strategies for dealing with these situations:

Finally, every person has different commenting styles. My supervisor’s strategy is to read as if she were a reviewer, an external person that doesn’t know you. If you don’t know this, it can sound as if she didn’t understand your research at all. But the point is: she reads your text carefully and checks if someone without the knowledge we have may misinterpret it. Sometimes small words can change the meaning of what you want to say. Be prepared for this, and don’t be afraid of asking questions.

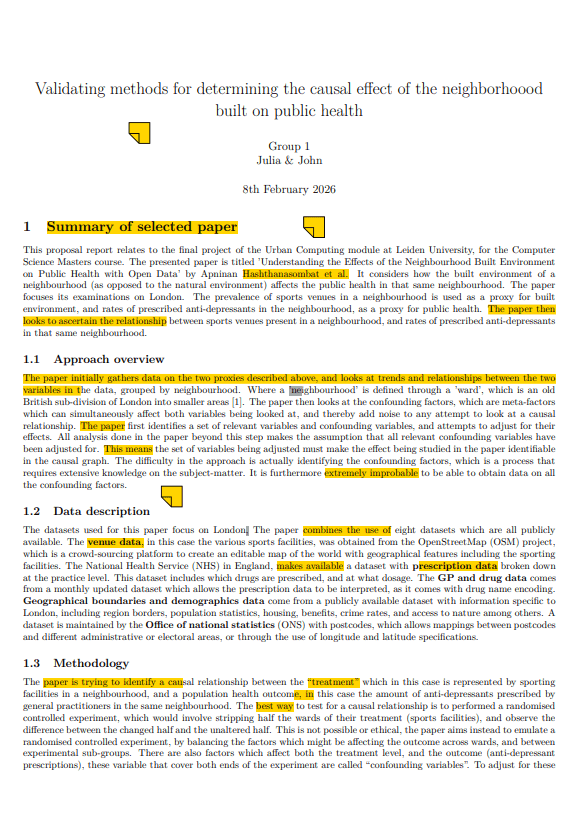

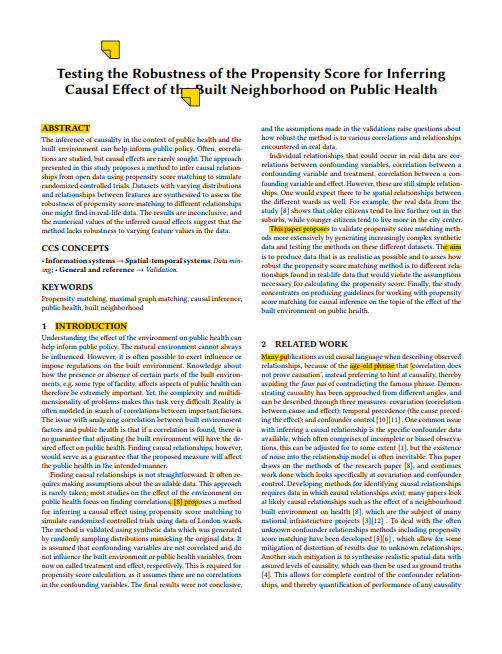

I went dug around my overleaf archive and found my own project proposal and report of the course I’ve been teaching during my PhD. The assignment was to design and carry out a research project starting from an existing paper. It’s like a mini-research project. Find the PDFs with my comments here. I hope it makes the explanations in this blog clearer.

As always, please reach out if you have questions or additions!